What's Your True Chronotype?

Our modern, plugged-in lifestyle has kind of messed with our chronotypes. Here's why you may need a reset.

We all know morning larks, people whose minds are whip-sharp early in the day, and night owls, who shine their brightest in the evening. Most of us fall somewhere in between, and you probably know which category you naturally lean toward.

Where do these tendencies come from, biologically speaking? And how much control do we have over them?

What is a chronotype?

Whether you’re a morning lark or a night owl is generally less about personal preference and more about your genetics, and your stage of life. This genetic predisposition is called your chronotype, and it comes from the Greek khronos, meaning time. Your chronotype is determined by clock gene variants, including a gene called Per3.

In sleep science, chronotype refers to a person’s preferred rising time and bedtime, their biological disposition toward the timing of activity and sleep. Although all humans are diurnal, clearly there’s a lot of variance.

“Our chronotype is determined by the phase of our circadian rhythm [our biological clock], and our sensitivity to external cues,” says Azure Grant, PhD, and physiologist. “It impacts our levels of alertness and motivation throughout the day, including the time of peak athletic performance, hunger and satiety. It affects stress, even blood pressure.”

Most of the systems and processes in our bodies run on internal clocks that generate circadian rhythms, cycles that repeat each day. One of the most familiar ways we experience circadian rhythms is through their impact on our sleep-wake cycle. “These biological clocks are made of tiny molecular machines that respond to a combination of external cues, like sunlight, temperature, or food, but they will also keep running in the absence of those cues,” says Dr. Grant.

“Some people’s clocks run a little faster/shorter than 24 hours, meaning in the absence of external cues they wake a little earlier and get tired a little earlier each day. Those are your larks, your morning people.

“Night Owls, on the other hand, have clocks that run a little slower/longer than 24 hours, meaning they wake up a little later and get tired a little later each day.” Researchers suspect that owls might also be more sensitive to external cues, such as light at night.

“If we were all kept in the dark, without any social cues or societal structures — ‘timekeepers’ like the start of a work or school day, lunch or dinner time — we might all end up running on our own preferred time tables that were wildly different from one another!" Dr. Grant says. "It’s those external cues that keep us all on roughly the same schedule.”

Circadian rhythm vs. chronotype

Circadian rhythms and chronotypes both play a unique part in your sleep wake patterns, but there’s a subtle difference.

Circadian rhythms refer to your internal clocks that control your sleep-wake cycle. Chronotypes, on the other hand, can be thought of as the way circadian rhythms play out in your everyday life. "Think of your chronotype as an aspect of your disposition,” says Dr. Grant. "For instance, if you’re an introvert, you can choose to live a more extroverted lifestyle, but because it’s not your natural inclination, you'll likely find yourself coming back to your natural preference again and again — and being healthier and happier when you do." When you're aware of your chronotype, you can turn it into a productivity tool to help you figure out the best times of day to take on certain tasks.

Here's how to identify your chronotype, how it changes with age and exposure to timing cues, and how to live more in sync with your internal clocks.

What is my chronotype?

Here’s how you can gauge your natural chronotype preference: “Imagine a week in which your phone, laptop, alarm clock, smart watch, and TV are all stowed away in a locked vault,” says Dr. Grant. “Your evenings at home are by firelight rather than fluorescents. When do you think you would fall asleep? When do you think you would wake up? How sure are you?"

Most of us are so used to plugged-in living that we don't really know how our bodies would feel without the constant pull of checking socials, sending one more email, or depending on an alarm to wake us up in the morning.

Dr. Grant points to an interesting study in which the internal circadian timing of 8 participants was assessed—first during a week of normal daily routines (work, school, social activities, etc.), and then after a week of outdoor camping (in tents, no constructed environment, with only sunlight and campfire light, and no technology present) in the Colorado Rocky Mountains.

The study found that with exposure only to natural light, participants’ internal circadian clocks synchronized to solar time: “The beginning of the internal biological night occurred at sunset and the end of the internal biological night occurred before wake time just after sunrise.” In addition, “later chronotypes showed larger circadian advances when exposed to only natural light, making the timing of their internal clocks in relation to the light-dark cycle more similar to morning types."

Researchers believe the findings have important implications for understanding how modern light exposure patterns contribute to late sleep schedules and may disrupt sleep and circadian clocks.

One of the best ways to figure out your chronotype, says Dr. Grant, is to incorporate tech-free outdoor time (including sunrise light and dark skies at night) into your next free weekend. If you can't spare a weekend in woods, you can take this quiz.

Can I change my chronotype?

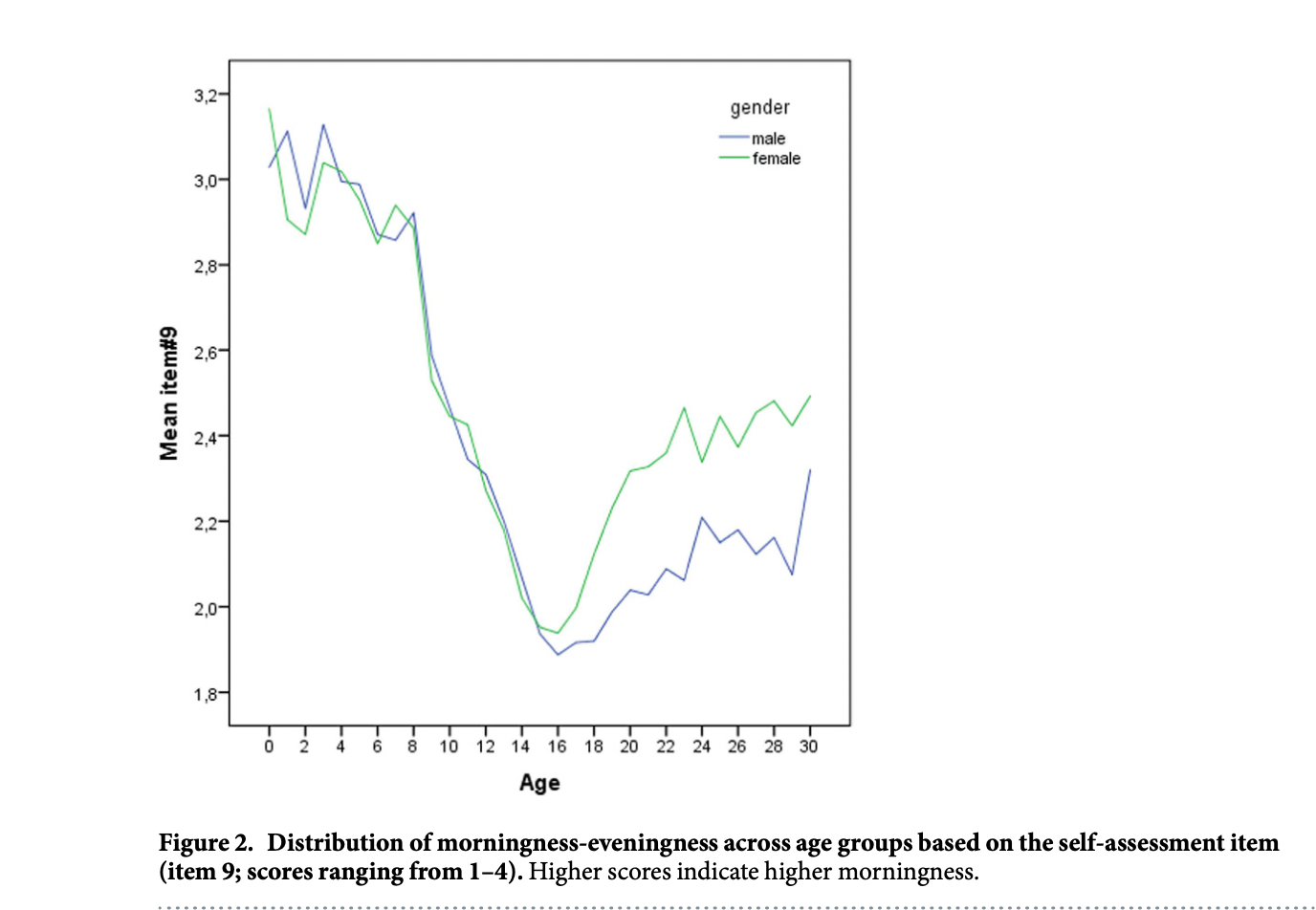

The short answer: not really. Though most people's chronotype does shift earlier as they get older.

Teens tend to be night owls, with circadian clocks that are delayed by several hours compared with children and adults. Most people gradually advance their circadian clocks to their adult state by age 25. After that, studies show that chronotype is fairly stable across adulthood (one study found that it advanced 10 minutes earlier over a period of 7 years). Many people find that they become more of a morning person as they get older. But it’s not a process you can forcibly accelerate.

Each chronotype has its benefits and drawbacks, but according to Dr. Grant, night owls unfortunately seem to have some extra challenges. For example, adolescents with late chronotypes are at greater risk for mood disorders, risky behaviors, missing class, and lower grades, and these tendencies may persist into adulthood, with grown-up night owls at greater risk for social jetlag (the discrepancy in sleep patterns between weekdays and weekends), burnout, and depression. It's thought that social factors and early school and work start times likely contribute to these effects.

"It’s unclear if the culprit is a mismatch between true chronotype and an individual’s choice about when to sleep, or something inherent about being a night owl," Dr. Grant says. "Does being a night owl predispose you to health issues, or is it simply hard to be a night owl in a morning world?" That's still a mystery.

The working world is certainly geared toward morning people. "Would night owls have fewer health issues if they weren’t subject to chronic circadian disruption? Does the extra sensitivity that night owls appear to exhibit to external cues like light and food underlie much of the night-owl phenotype, and is that sensitivity to disruption what ends up hurting owls?" We still have much to learn.

Working with your chronotype

Understanding your chronotype can help you work with your own sleep-wake pattern and figure out things like when you’re most focused for work or most creative, the best time to exercise, your patterns of energy slumps, even your best meal times.

“Despite the sleep challenges associated with the pandemic, work-from-home does provide the option for many to choose when they sleep and wake,” notes Dr. Grant. “This could serve as a model for a future where people, especially young people, are not as disrupted by having to attend early morning classes. For adults, fewer early morning meetings, no sleepy commute, and a chance to work when you feel in the zone can be considered a silver lining."

No matter your chronotype, getting morning light, keeping stable meal and activity times, and meaningful social interaction can help you stay healthier, says Dr. Grant. And it’s not just what you do — it’s also what you don’t do. Late meals close to bedtime and bright light late at night contribute to metabolic dysfunction whether you're a lark or an owl. "Strategies like red-shift for screens, intermittent fasting, early dinners, and reducing carb-intake in the evening can help reduce the risk of temporal disruption,” Dr. Grant says.

Lauren Duffell, expert sleep coach, agrees: "Artificial light after sunset plays a huge role in elongating our natural rhythms. I recommend turning off overhead lights when the sun goes down and using lamps with warm and dim incandescent lighting," she advises. If you're lucky enough to have a fireplace, she says, "use that or candles to create a calm glow for your evening unwind, as it prepares your hormones to create a better sleep for your brain and body. Blue-light blocking glasses [orange or red colored] are useful in the evening if you must use tech, or want to enjoy a movie. Progress over perfection!"

You can choose to live on a schedule that's different from your true chronotype, but the bigger the difference between the two, "the more you'll negatively impact every aspect of your health,” says Dr. Grant.

Bottom line: It’s better to work with your body’s natural rhythms than to fight them.